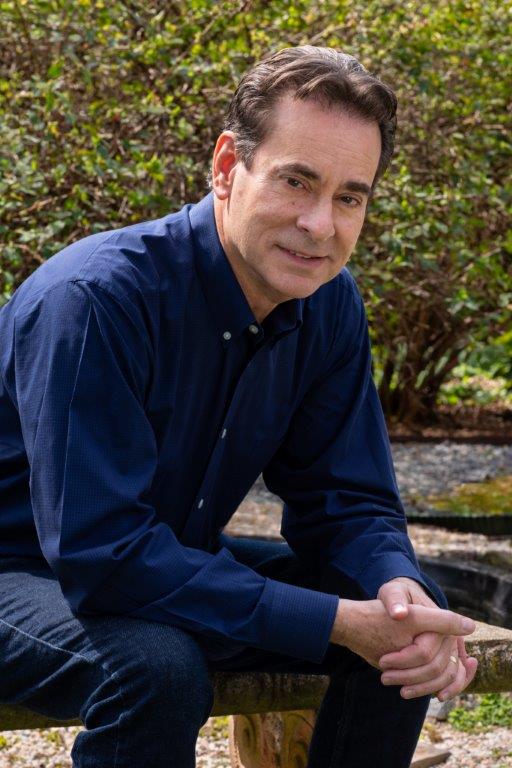

Rob Gentile was dead for more than three minutes. At least, that’s what he was told. He doesn’t remember anything about the night he had a massive heart attack.

Gentile, 57, slipped into a coma for four days after being resuscitated. He does remember waking up in the hospital last year and being told his heart was failing. After months of cardiac rehabilitation and medication, he realized that he only had two options: stay hooked up to a machine or get a new heart. He chose a transplant.

After being placed on the transplant list, Gentile’s failing heart needed help pumping blood to the rest of his body. With any other doctor, he would have undergone open-heart surgery to get a device that also could weaken his body and potentially make him unable to have a heart transplant. But his doctor had other ideas.

Dr. Valluvan Jeevanandam, professor and chief of cardiac and thoracic surgery at the University of Chicago Medicine, proposed that Gentile become a test subject for a new device he was testing at the hospital called the NuPulseCV iVAS. Currently the size of a lunchbox, it would keep his heart pumping, without open-heart surgery, until he got a new one.

The only downside was that it was in its first phase of human testing and had only been tested on pigs, cows and one human. Gentile was told to think about it and was handed a document the size of a phone book containing the risks, benefits and procedure.

“I thought I was going to die anyway,” Gentile said. “I looked at it and all the risks and benefits, and I decided to do it. … It was the best move I ever made in my life.”

About 5.7 million adults in the United States have heart failure, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Each year, about 100,000 people nationally are diagnosed with advanced heart failure and require some sort of mechanical support, a September news release from the University of Chicago Medicine says. The hospital did 36 heart transplants last year, Jeevanandam said.

Dr. Douglas Mann, a cardiovascular expert and the chairman and chief of the cardiovascular division at Washington University in St. Louis, said he doesn’t believe the new device will replace current technologies but thinks it will be another option that will give doctors flexibility in how they support their patients.

“With the spectrum of devices, the nice thing about this technology is the patient can go home with it,” Mann said. “I think this is a step forward. It will require larger-scale trials to see the durability of it, but I think it’s a really innovative and encouraging technology, and it would be great if the safety profile of this is acceptable.”

The device must successfully complete three phases of human testing before it goes through a Food and Drug Administration process that evaluates safety and effectiveness. Currently in phase two of testing, it could hit the market in 2019 if it passes each level.

Right now, the left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, is used as a longer-term solution for patients who may stay on the device for the rest of their lives. This procedure requires the chest cavity to be opened so a mechanical pump can be installed. The LVAD is worn like a backpack, and the tubes must be kept clean to avoid infection.

“This makes it difficult to do transplants because you have to go into the chest twice,” Mann said. “(The iVas) has the potential to provide temporary mechanical support to a group of people who might have no other option than an LVAD.”

In an emergency situation, the intra-aortic balloon pump is a short-term solution to stabilize the patient. It is inserted through the groin and requires the patient to stay at the hospital hooked up to a garbage can-sized helium pump console. The device is usually removed after 48 hours and serves as a bridge to recovery, transplant or an LVAD.

The new device, which goes under the collarbone and comes out the left abdomen, could help patients who need less assistance keeping their hearts pumping. The iVas is not as powerful as an LVAD but can be worn longer than a balloon pump and helps the patient’s heart continue to pump until it is time for a transplant, Jeevanandam said.

Gentile and other patients who volunteered to be tested in phase one had to remain at the hospital for observation until they received their transplants.

ing,” Gentile said. “It saved my life, and I think that it allowed me to be mobile and continue to exercise and stay healthy for my transplant.”

Now, phase two patients can go home with the iVas while they wait for a transplant.

Tom Gnadt, 52, of Elmhurst, walked through the halls of the University of Chicago Medical Center with an iVas that was installed Jan. 20. He has been at the hospital for nearly a month and is waiting for a heart and kidney transplant. Four days later, he completed three laps around the floor.

“It’s good to get up and walk around,” Gnadt said. “I’m breathing a lot better. We’ve been watching my oxygen levels since I got it, and last night I didn’t even need the oxygen mask.”

Gnadt left the hospital with the iVas last week and another patient was also waiting to go home soon if all goes well.

Phase three will allow the device to be implanted in a wider population of patients with heart failure. During each phase, design and software is expected to be improved so the device can hopefully become smaller, lighter and more patient-friendly, Jeevanandam said. He hopes the device will be ready for the FDA review in a year. So far, 13 patients have received the iVas, nine of whom have had transplants.

“It’s less pain for the patient and it’s less time for rehabilitation, so they can get back to life quicker,” said Jeevanandam, whose team helped develop the device. “For some older patients, they can’t tolerate a big operation, and this is an operation that they could tolerate.”

Jeevanandam has been developing, testing and regulating circulatory support devices for about 25 years, and the iVas is the most recent improvement on the balloon pump, which has been used for 50 years. LVADs have been used for almost 20 years.

“I wanted to see if there was a better way to support patients other than continuous flow pumps,” Jeevanandam said. “They work great and they’re fantastic and can save lives, but because of the complications, we reserve them for very sick patients, and we at the University of Chicago tried to figure out if there is a better way to support these patients that is less invasive and has a lesser complication profile.”

Gentile, a Charlotte, N.C., native who is living in Chicago until May to complete his treatment, received his new heart last June and has not had any major incidents so far.

“It’s cool to be a part of history, and they’ve had great success with it,” Gentile said. “There’s nothing else like it out there.”

This article originally appeared on Chicago Tribune Link to original article here.